Every American Tracked by 2029?

A few weeks ago, U.S. Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. stated that “every American should be wearing a wearable within four years.” While that future is far from certain, tech giants are already moving as if it’s inevitable. Samsung, in particular, is accelerating its push into digital health.

This week, Samsung said it’s buying Xealth, a U.S. company that helps hospitals use digital health tools. Xealth already connects more than 500 hospitals with over 70 health technology partners. The strategic goal? Tie Samsung’s wearables—like the new Galaxy Watch 8 series (hands-on) and Galaxy Ring (review)—more directly to clinical care.

When Wearables Start Making the Rules

As someone who reviews tech products, this seems like an exciting step forward. But it also brings up real concerns. I’ve tried out a bunch of wearables over the years, and one thing I’ve noticed is how easy it is for people to get overwhelmed by all the health data they throw at you. Features arrive before people fully understand them, leaving us to rely on marketing claims, enthusiast tutorials, and best guesses. And the emotional burden of “owning” your health without proper guidance is real.

What worries me most is how easily these wellness tools could be rebranded as medical infrastructure—without sufficient oversight. Many wearables are marketed with caveats: they’re for “awareness,” not diagnosis. But if data from these devices begins appearing in medical records, or worse, influencing insurance rates, we’re entering ethically murky territory.

Samsung’s acquisition of Xealth marks a shift from consumer health tracking to institutional integration. This isn’t just about new features; it’s about embedding wearables into healthcare systems. And the competitive advantage is clear: access to anonymized but large-scale health data, a ready-made hospital network, and legitimacy in the healthcare space.

Big Tech’s Shortcut to Healthcare

For years, companies like Withings have been slowly building out their own telehealth systems from the ground up. Samsung, on the other hand, is taking a shortcut, buying its way into an existing system that already works. It’s a bold move, but it also raises some uncomfortable questions about fairness, access, and what the long game really is. And it’s not like we’re seeing the same thing happen in places like Europe or Latin America, even though Samsung is big in those places too.

Meanwhile, other players are going smaller and more focused. Whoop is putting serious work into menstrual health tracking, while Amazfit is leaning into fitness niches with things like Hyrox workout modes. These are targeted bets, but they show how companies can meet real needs by honing in on specific communities.

Samsung’s approach is bigger and riskier. It’s not just selling gadgets anymore—it wants to be seen as a full-blown health data platform. In their press release, Samsung said the goal is to “bridge the gap between wellness and medical care.” And yes, they said “wellness,” not “health”—a subtle but telling choice that helps them steer clear of heavier regulations.

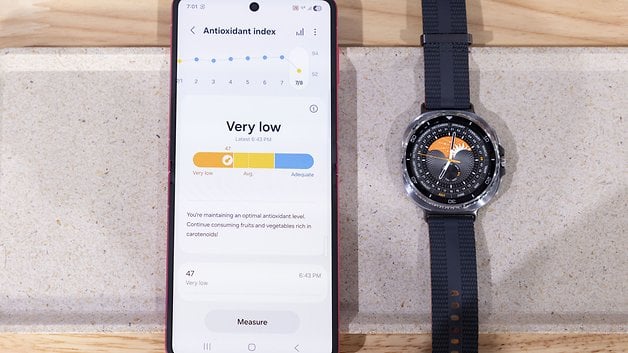

Here’s where it gets murky. Right now, features like “vascular load” or “antioxidant index”—which hover around alcohol, fruit, and veggie consumption—are being pitched as wellness metrics. But with the tech Samsung’s acquiring from Xealth, those same numbers could quietly start showing up in your medical records. And that shift? It could happen with barely any notice, let alone real consent.

When Wellness Becomes Policy

There’s also a bigger issue here: if health systems start leaning too hard on wearable data, they could end up leaving out the people who don’t use these devices or can’t afford them. No tracker? “Bad” data? Suddenly, you’re not eligible for the same perks or care. The digital divide could turn into something worse: a health divide.

I don’t believe Samsung is deliberately building a dystopian health surveillance empire. But good intentions only go so far. Health data is deeply personal, and if it’s not handled responsibly, the consequences can be serious.

Take period and fertility apps. People are increasingly worried that the sensitive data these apps collect could be used against them. A study from King’s College London found that most top apps could share data with law enforcement, especially in places where abortion is criminalized. Another report from Cambridge warned that this data is also sold at scale, posing serious risks to privacy and safety.

So yes—today it’s all about “wellness” and antioxidant scores. But tomorrow? Those same tracking apps could end up in your medical records or even be used against you in court. Without transparency, consent, equity, and accountability built in from the start, we’re not innovating; we’re playing with fire.

The Xealth deal hasn’t closed yet—though it’s expected to sometime in 2025—but we can already see where this is going. As wearables become more entangled with healthcare, we’re going to need stronger safeguards: clear consent, real transparency, and systems that don’t punish people for not owning a smartwatch.

Just today, Samsung’s Senior Health Care Executive Hon Pak outlined the company’s ambitious vision on LinkedIn: a global health platform designed to address chronic disease, aging populations, clinician shortages, and fragmented data. Their solution? An AI-powered ecosystem that links wearables, smart homes, and clinical systems. Wellness and health data, once separated, are now being merged.

Samsung plans to launch an AI health assistant later this year to enable “proactive health management.” But what does that actually mean, especially when it’s built on wellness data that has largely existed outside traditional regulation?

Yes, Samsung will have to pass regulatory scrutiny if it wants to operate in more formal healthcare spaces. That responsibility lies with governments and regulatory bodies, and it’s up to them to ensure proper legal frameworks are enforced. But key questions remain unanswered: How deeply will Samsung’s devices be embedded into care delivery? Will patients be nudged—or required—to use Samsung products? Will competitors’ devices be supported, or is this shaping up to be a closed ecosystem?

We don’t know yet. But those answers matter. Because what we’re building isn’t just a better fitness tracker—it’s the next layer of healthcare infrastructure. And if we get it wrong, the consequences won’t be technical. They’ll be human.

If we’re heading toward the techno-future HHS Secretary RFK Jr. keeps describing, the bare minimum is that it works not just efficiently or profitably—but fairly.